A Curated History of the Grass Mud Horse Song

As I thought about how to kick off the China Meme Report, I was overwhelmed. The Chinese internet is huge–some 500 million people are logging on each day, and nearly half of those are using microblogs. As in Twitter, Chinese microblogs like Sina Weibo and Tencent Weibo are feeding grounds of some amazing memes.

As I thought about how to kick off the China Meme Report, I was overwhelmed. The Chinese internet is huge–some 500 million people are logging on each day, and nearly half of those are using microblogs. As in Twitter, Chinese microblogs like Sina Weibo and Tencent Weibo are feeding grounds of some amazing memes.

Fortunately, my interests in memes are pretty focused. I love the silly, funny memes of both the English-speaking and Chinese-speaking internets, but I’m particularly drawn to memes that effect social and political change. An internet meme that effects change? You mean a political meme?

Think about the Casually Pepper Spraying Everything Cop meme that popped up in response to #occupy UC Davis. Everyone in the West remembers that meme because it was so unique–it was a crazy, silly explosion of internet remix culture targeted at a very gross violation of human rights. As Xeni Jardin wrote, it was “Photoshop justice”, as the lulz culture of the internet struck back against the perceived incongruity of the officer’s actions.

Political memes can have real effects: the police officer and his chief were placed on administrative leave, and at least one U.S. Representative called for an investigation. (Of course, the memes existed within a broader discourse, but they certainly provided fuel.)

China’s Politically-Minded LOLCat

China’s Politically-Minded LOLCat

I’ve been fascinated by Ethan Zuckerman’s Cute Cat Theory ever since I read about it. You should read the full post, but the gist of it is this: social media that are effective for sharing pictures of cute cats are also effective for spreading political messages. He cites the “brave and noble LOLCat” as the cute cat par excellence, which has spread and continues to be funny for years.

In a recent post on my blog, I made a suggested addition to Zuckerman’s theory. On the heavily censored world of the Chinese internet, memes are often the only way to get a message out there. The very nature of a meme–absurd, obscure humor; frequently remixed; stickiness–makes it almost impossible to censor by both human beings and computers (both of which Chinese social media sites leverage frequently). So while the Cute Cat Theory suggests a distinction between cute cats and activist messages, what I often see China’s internet is that the meme is the message. In other words, the cute cat is a form of activism.

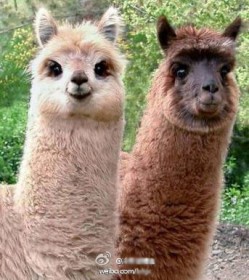

The creme de la creme (meme de la meme?) of political memes in the Chinese internet is, paws down, the noble Grass Mud Horse. Pronounced “cao ni ma” in Mandarin (草泥马), it sounds an awful lot like another “cao ni ma” (操你妈), a an extremely vulgar slur against one’s mother and a popular insult hurled by Beijing cab drivers. Modeled after an alpaca lama, the Grass Mud Horse is the most noble of the Chinese internet’s ten mythical creatutes, and it engages in constant battle with the evil river crab. For “river crab”, pronounced he xie (河蟹) sounds an awful lot like another he xie, meaning “harmony” (和谐), as in the “harmonious” censored internet that exists behind the Great Firewall.

Like the LOLCat, the Grass Mud Horse has amazing staying power. Its song was profiled by Rebecca MacKinnon and mainstream media like the New York Times and CNN as long ago as 2009, but it is alive and well with breathtaking variety. Oiwan Lam for Global Voices looked at the amazing discourse within China. Three years later, in China today, I’ve seen them on tattoos and cars, in stores, and of course online, where even casual pictures of llamas are referred to as Grass Mud Horses. If not ubiquitous, it certainly feels like it.

The Grass Mud Horse Song: Remixed and Remixed and Remixed

The Grass Mud Horse has many manifestations, but my absolute favorite is the Grass Mud Horse Song, which makes a fabulous introduction to the world of China’s internet memes. It’s an asburd children’s song (adapted from the Chinese Smurfs theme song) that tells the tale of these beasts in the mythical desert of Ma Le Desert. (The Ma Le Desert, naturally, is a play on words referring to your mother’s most delicate bits.) And then along come the river crabs, whom the horses must do battle with for freedom.

Recently, Ai Weiwei posted a video of himself singing along, bringing the song to prominence once more in the West. He sang in response to his followers’ request, after so many people turned up to donate money to support his tax case. But it was only the latest in the remixed, participatory world of China’s political memes, which have a unique character.

On Ethan’s suggestion, I plan to blog weekly on issues around China’s memes, and some of the amazing catches I’ve made while exploring social media sites (though I focus most on Sina Weibo, where most memes amplify). I’ve created a system, which I’ve dubbed the “meme net”, for catching the most interesting ones before they disappear into the ether, a real risk in an internet where posts and videos mysteriously vanish in a matter of minutes if they’re deemed too sensitive or become too popular and incendiary.

But there’s time for more theorizing and explaining later. Without further ado, I present to you a small sample of the breathaking variety of manifestations of the Grass Mud Horse Song. Keep in mind that while I’m often embedding YouTube videos for convenience for Western readers, these videos also exist wthin the Chinese Internet. In fact, if you starting typing in “Grass Mud Horse” on Youku, China’s YouTube-like service, the first suggested search is for this song. And no wonder: it’s been played and forwarded tens of thousands of times.

This, as far as I’ve been able to glean, is the original Grass Mud Horse Song. YouTube user skippybentley has done a fine job of adding translations and explanations of what you’re hearing. The subtitles are a common convention in China, where different people speak different dialects but read the same common language, but they also help show Mandarin speakers the different puns going on. Plus, it’s easier to sing along, karaoke-style (this is important–it makes the song catchier and easier to remix later).

But wait, there’s more. This is the rap/R&B version, which paints the tale of the Grass Mud Horse and Ma Le Gebi in epic fashion, where milk flows and beautiful women skillfully sing and dance of the Grass Mud Horse tribe. Once again, skippybentley has provided helpful translation of the song’s wordplay and meaning.

In London, activists fighting for a free Tibet played on the smurf theme by advocating for “Serf Emancipation”. They dressed up as smurfs while dancing to the song of the Grass Mud Horse. It’s important and characteristic of many of China’s political memes–these memes leap off the internet and into the offline world, whether as Grass Mud Horse plush dolls or, in this case, as an absurdist protest outside the Chinese Embassy.

While not a song, this “documentary” on the Grass Mud Horse tells the story of the Grass Mud Horse Song in a more narrative format–complete with an epic O Fortuna soundtrack as the Grass Mud Horses attempt to access more information on censored material like the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

Here’s a high school student singing the song.

Tom the Cat.

A CGI version.

A more choral, “soybean” version.

A Western college student’s reinterpretation of the tale, told in the form of a Grass Mud Horse attempting to enter a library for information.

And, of course, Ai Weiwei’s version, sung along with his iPad for good measure and then, oddly enough, censored.

So what’s the point? Why does the Grass Mud Horse matter? The meme is prototypical of the dark humor in China’s best political memes: subversive, punny, catchy, remixed to death, making them virtually impossible to censor. It’s just one of many memes, but it’s the most iconic, and it’s still going strong. Knowing how the Grass Mud Horse works helps us understand how other political memes work in China.

Really interesting reading.

and great collection of mude horses! Haha !

Thanks 🙂

Back in the days, this meme was so huge that Chinese netizens even created a new Chinese character to represent it : http://www.flickr.com/photos/isaacmao/3373071182/lightbox/

This new character immediately become a meme inside the meme and was followed by days of discussions, blog posts, press releases, articles, etc. about the legitimacy of such a word, its right pronunciation, etc.

An article in Guangzhou Daily : http://gzdaily.dayoo.com/html/2009-03/30/content_518890.htm

Another one in Sina news : http://news.sina.com.cn/s/2009-03-30/040817508267.shtml

The whole process of how “Mud Horse meme” became a word was documented in this timeline (in Chinese) : http://www.timeku.com/timeline/view/2361

For a list of all the pronunciation proposed by netizens, check this spreadsheet :

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0At0O9_GwRpdecFZhUXdON1dObHNidVpWbXdIWHpaV2c#gid=0

the best pronunciation is … “f***” !

Never under-estimate the power of the CaoNima !

Hey Clement! Glad you liked the post. This is really brilliant. Were you in China when the meme exploded? What was it like? I hadn’t heard about the new character that was proposed – I love it! I wonder if I can type it in on my iPhone…

Hi An,

I was in China but without any Chinese language knowledge, so i just followed it through foreign websites like danwei or chinageeks 🙁 Later Isaac Mao told me about the CaoniMa character.

About the input, i don’t think guys at Apple released this one 🙂 There is no dedicated pinyin yet