Kimchi and G-Nuts, or, a Taste of the Kampala Roll

88 Bar writer An Xiao Mina is living and working in Uganda this fall and researching the technology community and growing Chinese population in East Africa.

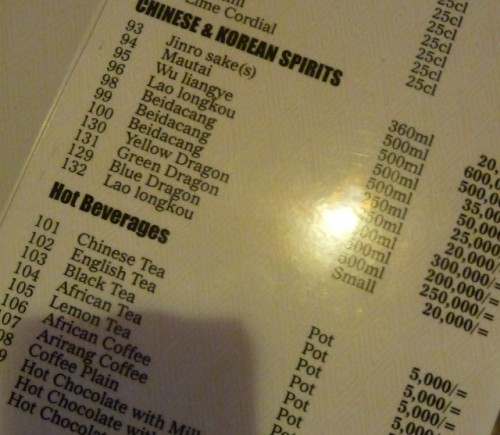

I was craving kimchi the other night, as did some of my colleagues. So we headed out to Arirang, a Chinese-owned Korean restaurant here in Kampala. There’s a large open space with sit-down tables (occupied mostly by Chinese, at least that evening), with private rooms on the other side, complete with low tables in the Korean style.

The food was quite good. Having enjoyed many Korean meals in Beijing, it seemed like a natural fit to me, especially as the restaurant had been founded by someone from Northeast China. But what stood out was the kimbap (a seaweed-rice-wrap dish, or basically Korean-style sushi) and the place white rice.

The white rice, which was served with a steamy bowl of kimchi soup, looked normaly enough. But as I poked through the grains, I noticed very soft g-nuts, or groundnuts. This latter is a popular Ugandan dish, one of my favorites, a sweet peanut that’s frequently mashed into a sauce. At first I thought they were mixed in accidentally, but my colleagues’ rice bowls also had them. It was unlike any white rice I’d had before, and I loved it. (The kimchi, too, was slightly different, though I’m still trying to get a handle on why it was different.)

The kimbap, which I’ve usually had with bulgogi and other meats, was stuffed with spam and groundnuts. I loved the extra crunch—sharper than daikon, which is usually the crunchiest thing I’ve had in a seaweed wrap—, with a unique blend of flavors. I couldn’t help but call it a “Kampala Roll”. Like the famous California Roll, it was made possible by the unique fusion of cultures in this diverse city.

As with many diasporas and migrant groups, Chinese communities and restaurants tend to go hand in hand. As the restaurants are open to everyone, fusion and mixing almost inevitably occur. The long history of Chinese in the Philippines, for instance, has given rise to popular Chinese-Filipino dishes like pancit (noodles), siopao (pork buns) and siumai (dumplings). The Filipino style is quite clearly Chinese in origin but you’ll never find the exact dishes in China. The same could be said of General Tso’s chicken and fortune cookies in the US, none of which I ever had when living in the mainland.

That doesn’t make the American or Filipino dishes any less authentic—that word, anyway, is pretty meaningless in the face of how often culture shifts and changes over time. It just makes them a new branch of food, originating from a Chinese migrant community and the local community. It got me thinking about “Have You Eaten?”, a recent exhibition on Chinese restaurants. Here’s a short snippet from a review I read:

Today, Chinese and Chinese Americans are important customers, as are other Asians and Asian Americans, and some restaurants are once again catering to newly arrived workers. How “authentic” they are, though, depends on how you define “authentic.” “It is and isn’t a return to the way things were at the beginning,” says Lee. She points out that with globalization, food is changing quickly even in Asia; what constitutes Chinese food is evolving.

A Ugandan friend living in Kampala tells me that Arirang started pioneering fusion, with additions like g-nuts into traditional Asian meals. Other Chinese restaurants, apparently, have followed suit, and I’m excited to start exploring that and cataloging just what Ugandan-Chinese food looks like. Both for my own interests—I’m a foodie at heart—and a more human-level look at the broader relations of China and Africa. There’s something important to pay attention to in this space (the number of Chinese I’ve met here is really striking), but food is also an important dimension. People have to eat too.