In Defense of Memes Defending Themselves

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3PDHyUEIqrA]

My talk at the Personal Democracy Forum at NYU’s Kimmel Center

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RDDi4Dj-EQI]

My talk at ROFLCon III at MIT

Political memes have been on my mind as of late. It started with ROFLCon at MIT and moved on to more discussions, Skype chats and journal entries. And I’ve just returned from the Personal Democracy Forum at NYU. Been a bit of a whirlwind as I travel around the country but seeing as I’ve lived on the east coast for so long, it was really nice to catch up with friends and see that side of the country again.

These two conferences couldn’t seem more different, looking from the outside. Just look at their respective web sites. ROFLCon, i.e., Rolling-On-the-Floor-Laughing Convention, is well known for being wacky and fun, even amidst the hallowed halls of academia. I met meme superstars like Antoine Dodson of “Hide Yo Wife” fame and Bear of “Double Rainbow” fame. By contrast, the Personal Democracy Forum’s superstar attendees included senator Ron Wyden and Todd Park, the Chief Technology Officer of the United States.

But in reality, both two-day conferences shared a deep concern with safeguarding and securing the future of the free internet, a concern that I think has come more and more to the fore in the past year. After living in China, I saw firsthand the consequences of a not-free internet. My co-panelist at the Personal Democracy Forum, Michael Anti, became famous after his blog was deleted. And blog deletion is just one technique to keep the internet under control.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3D2eh4xehc4]

The Grass Mud Horse Song, one of the most sophisticated political memes in China

I’ve obviously discussed China’s internet quite a bit these past few months, and I blog about it regularly, but during a lunch with the Tumblr Fellows at the Personal Democracy Forum, I was asked something new: Now that I’ve been observing meme culture in both China and the US, what’s the memescape like stateside? And that’s when I started to realized what it is about memes that makes them important.

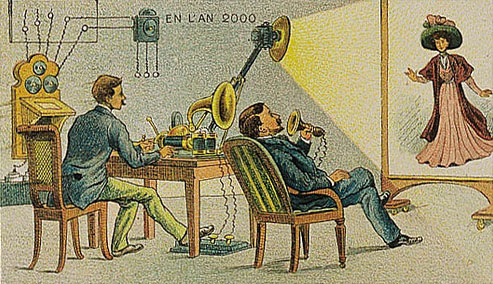

I may be shooting myself in the foot here (I’m just waiting for someone to come up with an ancient Roman analogy), but creatures like the LOLCat and the Grass Mud Horse are born on the internet. We could even say they’re of the internet. I recently stumbled across a Victorian artist’s rendition of the year 2000, and he pretty much nailed it–video chat, email, voicemail. That’s because much of the internet has analogues in the, er, analog world that are reflected in their names. E-mail, internet forums, the world wide web, web log. Tom Standage wrote a brilliant exploration the very blog-like virality of Martin Luther’s 99 Theses.

But what Villemard, that Victorian artist, didn’t predict was the noble LOLCat. How could he? Certainly, America’s Funniest Home Videos presaged the rise of YouTube’s mockery and self-mockery, and I often call memes the street of the censored web. The idea of a meme isn’t a new one, either. But who could honestly have predicted, before the internet took root, that a llama would stand as a symbol for internet freedom, or that a wacky video of a man raving about two rainbows could get over 30 million views?

And so it seems fitting to me that meme culture has become one of the most powerful tools against internet censorship in China (and, as I’m starting to note, around the world). Meme culture is the least understood by those who don’t use the internet. But culture is the right word here–like any cultural practice, the practice of sharing, remixing and laughing at memes seems completely odd to outsiders but totally natural to insiders.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f5lTRa_ZJn8]

The library destruction scene in Agora

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=icSwt4hUPTs]

Emperor Qin’s attack on a calligraphy-loving culture–and how calligraphy became a defense.

And as that culture is threatened, so do its proponents fight to preserve it. I think about that scene from Agora, about Hypatia and the Library of Alexandria. And then there’s the famous calligraphy scene from Hero, about Emperor Qin’s takeover of the rest of China. These scenes were no doubt dramatized, but part of what made them effective beyond simple depictions of destruction is that they show how people strive desperately to preserve their culture.

The good news? While scrolls and calligraphy can hardly do battle with knives and arrows, memes pack a little more punch. The relentlessness and breadth of China’s internet censorship techniques is well known. But so is the relentlessness and breadth of meme culture. The stickiness of memes, the way they inspire remixes and co-creation, their utter refusal to die–that’s a powerful tool against censorship. As I’ve witnessed in China, once a political meme sets hold in netizens’ minds, it just won’t go away. It will surface and resurface and resurface again, with dark humor that makes the serious issues a little easier to discuss.

I wish I had the prescience of that Victorian artist. I’m not good at predicting the future, but I suspect that the freedom fighters of cyberspace will come galloping in on LOLCats and grass mud horses, ready to defend our right to share silly pictures online.

—

And, as a bonus, here’s my interview with Nick Clark Judd at TechPresident on some of the mechanics of Chinese meme culture and language. Want to read more about Chinese memes? Be sure to follow the China Meme Report here at 88 Bar and check out my writing page for more of my writing on China’s political and social memescape.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHLxtErW4lY]