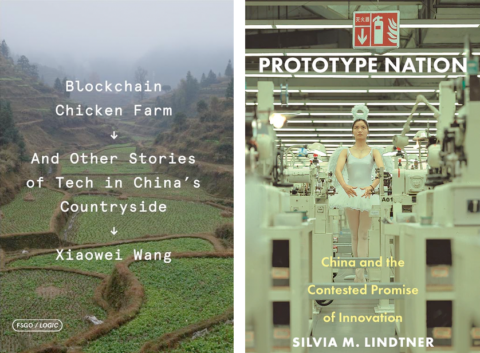

Looking at China and Seeing Ourselves: Two Ethnographies of Tech in China

Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in China’s Countryside

By Xiaowei Wang

FSG Originals, 256 pp.

Prototype Nation: China and the Contested Promise of Innovation

By Silvia M. Lindtner

Princeton University Press, 288 pp.

It’s really hard to get an on-the-ground view of what tech in China is like today. Coverage is often shrouded by fears of China’s status as a rising world power, or glossed over with the optimistic fervor that accompanies startup coverage worldwide. Wang and Lindtner, in their respective books, cut through these problems by deploying an ethnographic lens based on years of fieldwork. In both accounts, the author-observer is situated clearly, so we are able to see the world through their eyes and experience the human-to-human interactions as they did. In short, Blockchain Chicken Farm and Prototype Nation offer rare, honest glimpses behind the curtain of tech in China, by way of exploring its periphery and by delving into its underbelly.

Styled as a travelogue interspersed with recipes, Blockchain Chicken Farm investigates the geographical and metaphorical fringes of tech in China. Much of Wang’s travels take place in rural areas and villages, where they explore these places’ roles as consumers, adopters and producers of technology. They take us from the titular blockchain chicken farm to the China Number One Taobao Village, from a mountain village pinning its hopes on e-commerce to a mining town in Inner Mongolia. Wang’s conceptual explorations are no less thrilling, as they delve into the banality of corporatized surveillance, the prevalence of farming technology, and the interconnected US-China flow of material goods.

What differentiates Blockchain Chicken Farm from a travelogue (aside from its years of fieldwork) is that Wang always returns home from their travels. They don’t hesitate to connect what they see in China to their experiences in the US (where they normally live). This highlights the very real flow of ideas, intellectual property and culture that cycles back and forth between the two nations, particularly around tech. But they don’t just stop there, most of Wang’s chapters end on a reflective note, often linked to works of social theory, about what these technological developments mean for how we live our lives today. For example, at the end of a chapter on surveillance and predictive AI, they challenge the notion that any amount of data can really represent us, invoking psychiatrist and philosopher Frantz Fanon to rail against the idea of predictive policing.

The recipes that live in between chapters add a layer of whimsy and imagination to the book. Each starts off prosaically enough, with a research statement about how the culinary experiment came to be and a list of ingredients. Then, as we continue reading the instructions, the recipe takes a fantastical turn until we are, for example, frying up a soy bean fritter that has, encoded within its DNA, your flattering LinkedIn headshot.

While they share many of the same themes, Prototype Nation differs greatly from Blockchain Chicken Farm in two main ways. First, it is a deep dive into one place (the city of Shenzhen) and topic (hardware startups and the maker movement). Then, it is styled as a piece of research with a more serious tone and greater abundance of detail. Through a decade of ethnographic research, Lindtner shows us how the American idea of maker-entrepreneur was taken up and adapted by China’s government to further their shift towards a neoliberal individualism. Meanwhile, the US startup world latched onto Shenzhen’s status as a manufacturing hub and Special Economic Zone to create the fantasy of a new frontier, far away from the problems of the 2007-8 financial recession. This uncanny, transnational synergy weaves itself through the book, as another reminder that our world is an interconnected one.

One of the central tenets of Prototype Nation is that startups and the maker movement carry with them an “affect of intervention,” where “makers” are motivated by a sense of agency, believing that they are prototyping a better future and hacking the system for social good. But as we follow the trajectories of engineers and community leaders throughout the book, it becomes clear that makers simply reinforce the current neoliberal system and add to inequality of hidden labor. In one chapter, Lindtner joins a team as part of a startup accelerator program in Shenzhen. There she observes how entrepreneurs and projects are coached to become palatable to venture capital (aka massively profitable), and how two women “office managers” effectively run the entire program’s operations (from cultivating relationships with factory bosses to ordering parts off of Taobao for teams) without any real opportunity for advancement.

Another key part of Prototype Nation is Lindtner’s account and analysis of the idea of shanzhai (山寨) over the years. She deftly traces its roots from its scrappy but happy beginnings in and around electronics factories in Shenzhen where hardware designs are pirated and remixed, rapidly prototyped and produced, in a messy but level playing field. Then we follow along as shanzhai becomes rehabitulated into a romantic concept of open source hardware, particularly in the eyes of Western sojourners to Shenzhen. Lastly, we watch as both former shanzhai makers and the renowned Huaqiangbei district in Shenzhen distance themselves from shanzhai as they move into the world of intellectual property and branded products.

Read together, Blockchain Chicken Farm and Prototype Nation give a respectively broad and deep understanding of the lived experience of tech production in China. They focus on how technology is shaped by its creators and its users, and highlight how easily ideas and objects in the tech world seamlessly hop between the US and China. Both books offer a rare and honest glimpse into China and help us understand how the systems and nature of tech affects the way we live and grow every day.