Debunking myths about China state control & surveillance in the age of COVID-19

Editor’s note: Starting in January, Tricia re-connected with her former colleagues and contacts in Wuhan (where she did extensive fieldwork in the past) to find out more about the COVID-19 pandemic and the truth behind some popular myths that have been floating around on the Western mainstream media. Here, we document her debunking two such myths (with the help of Shayla Qiu and Reginald Zhu), with excerpts of her writing online.

Myth #1: China has a perfect state surveillance apparatus that’s being used to track COVID-19 cases step-by-step across the country

I had to travel earlier this month and this is how my movements were being tracked for the purpose of #COVID19 containment.

Follow @RadiiChina for more videos on #China! #coronavirus #COVID2019 pic.twitter.com/yHzdm7q6HF

— Carol Yin (@CarolYujiaYin) March 16, 2020

In response to this widely shared short video demonstrating QR code check-ins, data sharing between platforms and a personal health rating, Tricia writes:

The lack of context in which Carol Yin’s video [above] of using health codes in China is being shared on Twitter and linked to MIT Technology Review’s really good social distancing article seems to be creating confusion about how it’s actually being implemented…

As Carol Yin said, every city has their health code rating system (健康码) for COVID-19 to determine if one is “safe” or not to enter a specific building or area. The health code system (健康码) is not universal applied across China. It’s implemented in places that have had an outbreak.

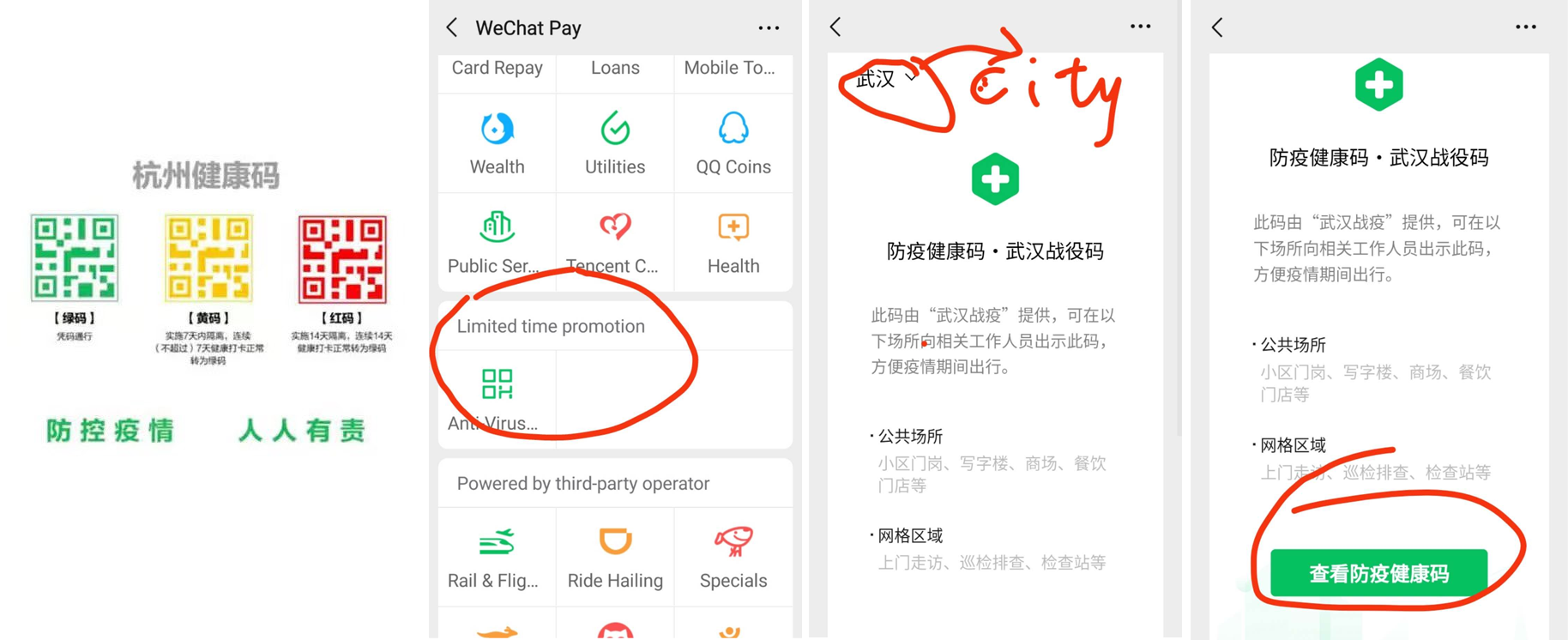

There are competing health code systems & it’s confusing people. We documented 6 competing codes that one woman had to use just to be “safe” for work: 1) Wuhan city code, 2) Hubei provincial code, 3) community (社区) code, 4) Alipay code, 5) Tencent code, 6) Guangzhou code…

People are complaining that all the competing codes are making it hard to get back to work or get around. Each system has their definition of what is “safe”— adding to the confusion. All codes work on a 14-day quarantine, but the day that the code gives you a “green,” which means you’re healthy, varies in each system…

The health code system (健康码) isn’t doing a continuous GPS tracking of a person. It’s tracking the entry and exit of a person into places, such as transportation, buildings, and cities through the QR codes attached to one’s Alipay or WeChat app:

AND there is another location system called 4G by their three largest cell providers that tells you what cities you’ve been to, NOT the exact GPS trace of your movements.

To enter a building such as an apt complex or your work place, they can request that you show them which cities you’ve been in the last 14 days. The user sends a message to their cellphone carrier and the carrier texts back which cities your SIM card has been in the last 14 days. The system is primarily built to reveal if someone has been to Hubei Province to not… Then to enter or leave a 小区 residential building (meaning one’s home usually), requires a temperature test, not a 4G or a heath code system scan.

Read her full Twitter thread here.

Myth #2: Authoritarian, top-down measures are the sole reason why China was able to slow the spread of COVID-19

As Tricia writes on Buzzfeed:

It wasn’t just top-down measures that successfully slowed the infections in Wuhan, it was also bottom-up, dynamic organizing in emergent, hyperlocal groups…

[Wuhan residents] utilized an existing social construct, the xiao qu (小区) group, which literally translates to “small district.” A xiao qu is an official designation from the city grouping together all the homes in a given area. Typically, a xiao qu captain (a volunteer or someone appointed by the property management) invites all residents into one WeChat group, which can range from 50 to 500 people in size. Wuhan has at least 7,106 xiao qu groups among its 11.08 million residents, many of which existed before the coronavirus took hold.

Once quarantines started, people realized that they could use the xiao qu to communicate with their socially distanced neighbors. And the hyperlocal network was born.

They shared information. Whenever a news report circulated on WeChat, the group would examine and vet it together, pointing to better, verified sources. When rumors about potential cures were shared, people would warn each other from trying them.

They shared uplifting quotes, memes, home exercise regimes, and recipes, but also asked their neighbors to go out and buy food or pick up medicine for them, a way of limiting group exposure. When an elderly woman without a smartphone told her neighbor that she had run out of food, the neighbor posted to the xiao qu group and her people donated portions of their groceries. When people fell ill, members fanned out into other WeChat groups to help find hospital beds and get information on caring for someone with the virus.

Read the full article: You Can Learn Something From The People Of Wuhan.

And be sure to check out the companion piece: How to Create your own #HyperlocalGroup.