A status update on China’s high-end industrial development

China recently announced it will begin producing and selling its first large passenger jet (since 1980 according to Wikipedia). In response, James Fallows penned two great posts, with accompanying charts, about what this means for China’s industrial development. Here’s his summary from the second post:

The chart was a shorthand for the theme I had developed in China Airborne: that the next decade or two of industrial development were likely to be a lot more challenging for China than the previous few (near miraculous) decades had been.

This past generation was when China brought hundreds of millions of people from rural poverty to inclusion in the global manufacturing-and-trading system, mainly at lower-wage, lower-tech assemblers for the world. A generation from now, is China likely to just be a bigger version of today’s supplier-to-the-world economic model? Or will it have moved into the high-value “rich country” industries that would give it its own GE, its own Apple, its own Siemens, its own Toyota? That is one of many dramas now underway in China’s evolution. And the question also includes whether it will have its own Boeing or Airbus. The C919 is a step in that direction, but this first step is mainly iPhone like, in assembling others’ components.

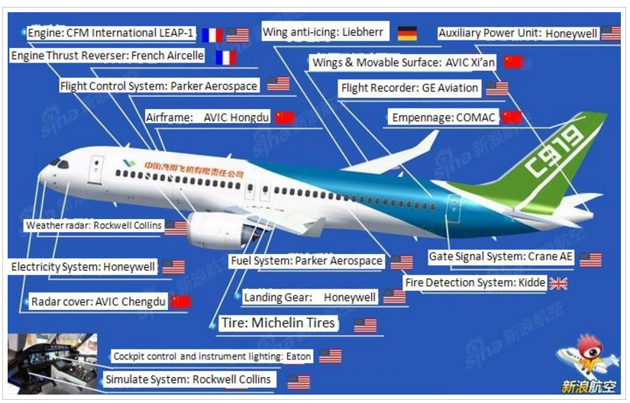

Now for the charts: first here’s a 2012 chart from Sina of where the C919’s parts come from:

And here’s where a 2013 chart about where Boeing Dreamliner’s parts come from for context:

Fallows’ summary of what all of this means:

In short, the charts show difference kinds of outsourcing at different stages of industrial development. The Chinese aerospace firms are assembling outside components because they have to. They can’t (yet) make them on their own. Boeing has been assembling some outside components because it chose to. It is now reassessing the consequences of that choice.

Read Fallows full commentary on the issue, starting here and then finishing here.