Dispatch from Shenzhen: selfie sticks, karaoke mics and Shenzhen-speed urbanization

Editor’s note: As part of her ongoing research, An Xiao Mina was recently in Shenzhen, visiting makers, manufacturers and the Shenzhen Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture. Below are some highlights from her recent Instagram posts, and stay tuned for the follow up post.

Above: Gao Lei demos his Exercise Toy for Grown-Ups, which he and his team prototyped using parts from Taobao and markets in Shenzhen. The gripper connects to the phone via Bluetooth and triggers actions on a game inside WeChat. He did initial business validation via Taobao crowdfunding and then sold the device on different Taobao shops. He collects user feedback in a small community of WeChat followers. Shenzhen’s network density of hardware producers made this idea possible, but so did a density of Internet users with electronic payment options. Like his game, it took a bit of the digital and physical to merge.

Above: Momax is an app designed for selfie sticks. Most selfie sticks I’ve seen have one of two triggers–a Bluetooth button or a cord that plugs into the headset jack. This app alleviates the need for a physical trigger altogether with a peace sign recognition algorithm – as soon as the peace sign is detected, a camera timer starts, the picture is taken a second or two later. This references a common gesture amongst east and southeast Asians when taking photos.

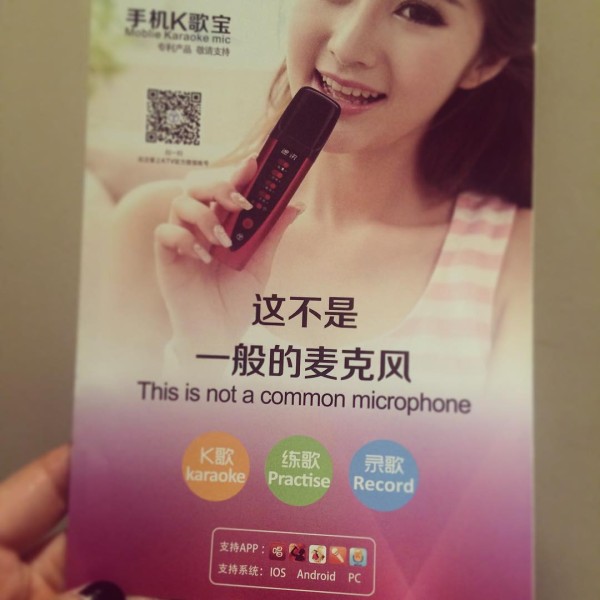

Above: The mobile phone took music mobile and, in so doing, it made mobile the ability to sing along to music too. Shenzhen Teana Technology Co’s mobile karaoke mics work with popular mobile apps to play music and record results via Bluetooth. When we talk about the new hardware of Shenzhen, we have to talk about its interconnectedness with our digital lives. Cell phone cases, selfie sticks, karaoke mics — these provide value because of how we use our phones and computers and why.

As Gao Lei noted, Chinese makers and manufacturers are often designing for the market they know best–and while it’s hard to imagine a karaoke mic doing well in the West, it’s easier to imagine success in China and other parts of Asia. The narrative of Chinese knock-offs needs to give way to a new (and more familiar) narrative: market-driven design.

Above: A kids’ maker playground in Shenzhen hosted by 搭搭乐乐 (one translation: Build Build Joy Joy). They teach making skills and robotics to kids from grammar school to high school. The classes are inspired by curricula in the US, and they are designed as an outside supplement to regular classes.

Above: What are the factors of urbanization in Shenzhen, the 30-year old, ~30m population city? How are they different from other cities in China, and other industrializing cities around the world? At the Shenzhen Biennale, ethnographer Mary Ann O’Donnell facilitated a bilingual conversation with scholars from the New School and locally who are looking at this issue.

One of the most important meta themes to keep in mind is that Shenzhen is largely a city of rural immigrants and largely a city of young people–post 80s and younger. They are forming and exploring multiple identities at the same time. What felt under discussed was the role of the Internet in all this; it seems impossible to discuss cities without discussing the Internet, and to discuss the Internet without discussing people’s daily experiences on the ground. Migrant workers ourselves, global creatives and scholars rely on apps like WeChat to stay in touch and collaborate, and afterward we all added each other on WeChat. Scholar Dr. Jue Ren presented a compelling vision for how the “digitizing individual” is breaking down the rural-urban dichotomy and essentially urbanizing the countryside by bringing in new tech and adopting urban tech practices in their home towns. I hope more urban studies scholars bring the Internet into their work (and the same of Internet scholars and urbanology).

Above: Ever since I saw Chinese solar panels outside a hut in northern Uganda, I wanted to know: how did they get there? Those solar panels and the phones they charged and even the 王老吉 drinks I found in rural northern Uganda started here in the dense streets of Guangzhou. Companies provide a full stack of shipping, packaging and translation services for both Chinese and African traders, and in the same building one can buy solar panels, motorcycles, phones and peripherals, brick building tools and diesel generators at wholesale–objects that arrive in Mombasa and Dar Es Salaam and then, by trains and trucks, making it all the way up to a shop in Gulu, Uganda, where they are bought and carried back to small villages along the Nile.

In this mall, one hears the constant sound of packaging tape and the thumps of cardboard. Some shops help with specific countries and personal shipments; others are more for wholesale. Some people prefer Chinese, English, French, and other languages I can’t understand. The global influence of the Pearl River Delta is difficult to overestimate, and its influence is the result of many “small” businesses working together, none of whom are centrally coordinated but all of whom are deeply interconnected.

Above: Christina Xu wrote about the role of QR codes in China and it’s been striking to see it for myself–QR codes for web sites, WeChat groups, contact info, payment. I remember wondering why anyone would use a QR code, and now I understand why. WeChat had made the process of exchange very simple–just a few taps and a scan–, and it’s reduced barriers that Chinese language speakers face with input–something it pioneered with voice chat. Previously, I’d only seen them used for paperless ticket contexts, like airplane check-ins and movies. This is what is so interesting to me about the global web: there’s always some way that people use technology that’s unexpected by Western standards and that takes off in a different cultural and technological context. I’d been a QR code skeptic myself till I read Christina’s article, and now I’m wondering why no one uses them in the US.

Above: 深圳速度–Shenzhen speed, as people here say, to talk about the pace of change and development. Maybe in English they’d call it a “Shenzhen second”. In a relatively young city, both by age of resident and age of the municipality and Special Economic Zone, the speed can be surprising, even by China standards. Walking around with one of the rare city natives, I was struck by how little she knew about the city herself. The pace of change, the city’s youth, the fact that most people in Shenzhen are not from Shenzhen–it helps set the context for the making and creating and manufacturing going on here. In many ways, it feels like a college town, where people come together with no historical connection to the town or pre-existing ties to each other. They find ties along other forms of identity, and they often use the Internet to build and maintain those ideas. They are, as scholar Dr. Jue Ren explained to me, digitized individuals in the context of a China that is moving from the danwei system to a more individualized society.

Above: Where does the selfie stick come from? It needs to be understood in the context of the Pearl River Delta, a rapidly developing region in China with an unmatched global influence. There is no one selfie stick, no one maker, no one distributor, no one seller. People in the phone accessories industry work together, they share ideas, and then surprises like the selfie stick emerge. Its popularity is attached to the smartphone, and it hasn’t waned: its utility in a rapidly changing world is in helping young people define and shape and explore their identities. They are far from home, far from old friends, growing up alongside 个体化中国–individualizing China. The selfie stick matters because each of us has the right to form and shape our sense of self, and in a world that often dehumanizes and disconnects us, in a world that changes faster than we can keep up with, holding onto that identity becomes critically important. It is a product of, by and for the Internet, and it reveals just how important the Internet has become in all corners of our lives. Photo by Doris Wang.

Above: After wandering the streets of the Pearl River Delta–Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Hong Kong–I started to wonder about the copycat narrative. There’s something very classed about the assumption that lower-cost goods are somehow culturally inferior and intellectually less rigorous. To call something a copycat is to assume that the original was an original at all, and not the result of a process of endless iteration and remix. The future is here, declared William Gibson, it’s just not evenly distributed. The makers of the PRD and the sellers who come from all over China and the world are distributing the future to people and markets long since ignored by dominant product platforms.

Selfie sticks should be banned. Forever! While at Giverny late last Spring, we were faced with crowds. Among the moronic idiot tourists were those with selfie sticks. Such a lack of respect for others was put into effect by these stick buffons that they cared not how many people they prodded and poked. Selfie sticks are the tool of narcissistic and moronic tourists. I had the bruises to prove it.

I think selfie sticks are great. They get in the way sometimes. But they are still great.

I don’t use selfie sticks for their intended purpose but to hold my phone while watching YouTube or video chatting and I have to say they come in handy for a girl with only one hand.

This is a great post–thank you–but isn’t Shenzhen’s population closer to 11M?

loving the selfie stick info!