Coming of age in a culture of information paternalism in China

Editor’s note: this is a summary of some of the ideas that are presented in Tricia’s recent talk the Berkman Center, Talking to Strangers: Chinese Youth and Social Media. The video of the full talk is now online, and we highly recommend watching it in its entirety.

Tricia’s research discusses how Chinese youth are experiencing their coming of age in a culture of information paternalism. That she does not call it censorship is an important distinction, because in China today, the dominant narrative around control is “father knows what’s best for you.” Here, “father” can refer to an actual teen’s parents, relatives, teachers or the Chinese government.

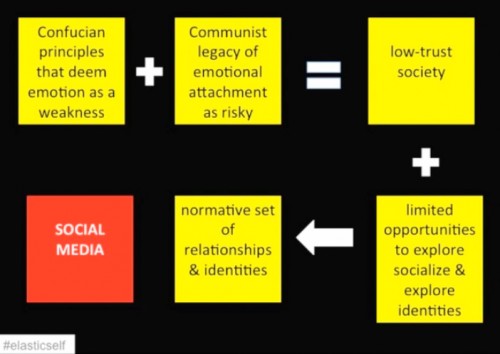

This dense sphere of paternalistic control (on top of the historical-cultural forces at work) drives Chinese teens to seek alternate channels of expression and socialization online:

To effectively escape, Chinese teens experiment with their identity and grow up online by cloaking themselves under pseudonyms and login handles. This type of experimentation, the polar opposite of on and offline real-name social networks, allows youth to develop what Tricia calls an “elastic self.”

One great finding was that Chinese youth had developed an entire chain of rituals to convert an anonymous social interaction into a real life close connection. Interactions begin by finding people on social networks with similar interests or horoscopes. This then turns into casual conversation and e-cards for birthdays. That in turn leads to people sending little physical gifts to each other to verify a physical address. And then people will share their phone number, followed by a photo and then, lastly, a 30-second video conference to ensure the veracity of the photo.

In the same way Chinese youth are finding each other online, they are also discovering more parts of themselves. Tricia structures the phases of the elastic self as 1) exploratory, 2) trusting, and 3) participatory. Only in the last phase do teens become politically active, and not everyone makes it to third phase.

But Tricia is careful to highlight that most people in China are not going online to vent about the government. They are, for the most part, there to hang out and enjoy themselves [which is, frankly, what we all do on the internet around the world].

The talk ends on a high note: the elastic self allows this new, online generation of Chinese youth to become more socially complex, coordinated and independent. And that can only be a good thing for this world.