Locusts and Pandas and Bears… 哦麦 (o mai)!

Those of us following China have noticed the increasing tensions between Hong Kong and mainlanders. More and more mainland women have been crossing the border into Hong Kong to have babies, where their children can expect to receive better healthcare and a coveted Hong Kong passport, which offers more freedoms and privileges. Hong Kong citizens on the other hand are protesting vociferously that mainlanders are taking jobs and resources without contributing their fair share.

Those of us following China have noticed the increasing tensions between Hong Kong and mainlanders. More and more mainland women have been crossing the border into Hong Kong to have babies, where their children can expect to receive better healthcare and a coveted Hong Kong passport, which offers more freedoms and privileges. Hong Kong citizens on the other hand are protesting vociferously that mainlanders are taking jobs and resources without contributing their fair share.

“Locusts,” they’re calling them. It’s a slur meant to conjure up the image of buzzing, swarming locusts coming in and eating up everyone’s resources. Sound familiar? As a Californian, I can’t help but notice the striking resemblance to issues of immigration in the United States, as states like Arizona and Alabama enact stricter rules against illegal immigration.

It ain’t easy being a memeologist, especially when working in a medium that’s not my native tongue. On Twitter, I can easily scan through dozens of tweets in a few seconds but on different Chinese social media, I have to be more strategic. Part of my strategy is knowing when memes will pop up. As soon as I heard about the locusts incident, I knew it would be a meme. What tipped me off?

- It was sparking strong emotions across the country. No doubt, calling an entire group of people “locusts” will provoke anger and frustration. And since a site like Sina Weibo often serves as a space for letting off steam,

- But there are lots of issues people get frustrated about. What this issue has is very strong imagery. From the protests in Hong Kong to the image of pregnant mainland women shuffling across the border to locusts, it’s rich with imagery.

- The most important part, however, is that there’s an animal involved. Locusts. We all know what they look like, and they can easily be turned into a meme. I’ll talk more about this later.

And so, of course, I knew a meme was afoot. What did I find? Locusts, and lots of them. A full page ad, shown above, appeared in Apple Daily, one of Hong Kong’s newspapers, and it began circulating on the internet. Here’s the translation from the Wall St. Journal: “Hong Kong people, we have endured enough in silence. Are you willing for Hong Kong to spend one million Hong Kong dollars every 18 minutes to raise children born to mainland parents?”

The ad, according to the Journal, was the work of one man who organized an online campaign to raise 100,000 Hong Kong dollars (12,900 USD). It was a watershed moment in a series of anxiety-ridden images that began popping up in papers and online.

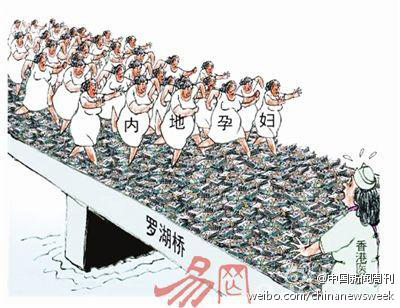

I first noticed this, showing a swarm of “mainland pregnant women” crossing Luohu Bridge, which connects Hong Kong with the mainland city of Shenzhen:

And then this:

And this, showing a man dropping a temporary residency permit and proudly brandishing a permanent residency permit:

These comics reflect the fears of Hong Kong residents, who perceive mainlanders as swarming their land and taking money and passports with them while giving birth to their locust children. We don’t often see such baldly racist or classist comics in the US anymore, but a recent one comes to mind. In Michigan, congressional candidate Pete Hoekstra gained notoriety for airing a baldly racist ad in the Superbowl with a pan-Asian woman in a bad accent claiming she’s stealing American jobs. Sites like Funny or Die panned it immediately, with one parody featuring actress Ali Wong giggling like Chun Li in Street Fighter.

Likewise, mainlanders took the classist, fear-mongering advertisement into their own hands. They took the original ad and distributed a blank version:

It was quickly remixed. A lot. I came across dozens and dozens of hacked, remixed ads, some being retweeted almost 100,000 times. Here are a few.

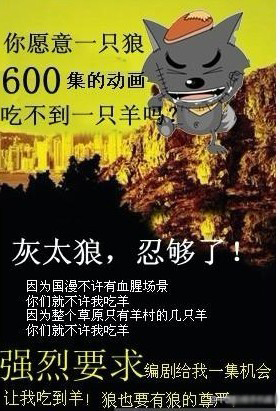

This one advocates for poor Big Big Wolf, who hasn’t had a chance to eat the sheep after some 600 episodes of Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf, China’s most popular homegrown cartoon. Like Wile E. Coyote, the wolf never eats the goat, and the advertisement says he’s endured enough. “The wolf also deserves the dignity of being a wolf!” it proclaims:

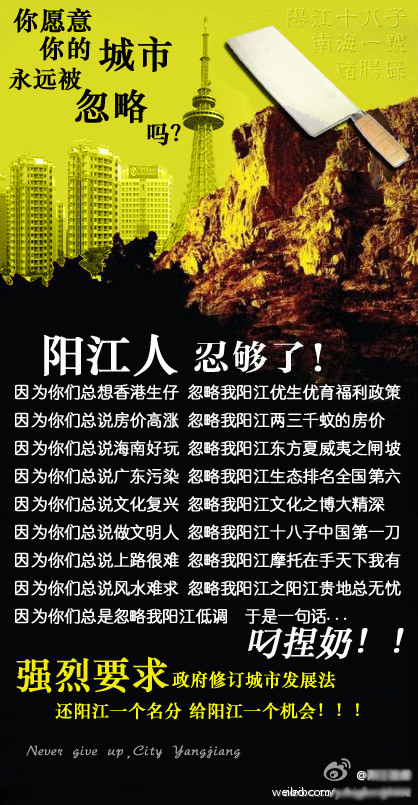

Most of the memes are more serious and they reflect deep-seated fears. This one asks: “Do you intend for your city to always be neglected? Yangjiang people have endured enough!” Yangjiang is a district in Guangdong province, the province adjacent to Hong Kong. It makes claims like “Because you always think about a life in Hong Kong, you’ve neglected the benefits of welfare policies for raising children in Yangjiang” and “Because you always say culture is reviving, you neglect the extensive knowledge and deep scholarship of Yangjiang.” Time to let go of mother’s breast and give Yangjiang a chance. Interestingly, one little sentence in English says, “Never give up, City Yangjiang.”

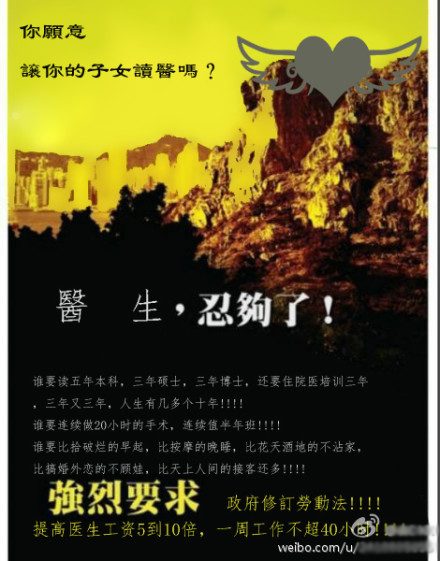

Or this: “Do you intend to let your children study medicine?” It advocates for a 5-10 fold increase in wages for doctors and a cap of 40 work hours per week:

“I’ve had enough of the counterattack from Hong Kong’s pregnant women!”:

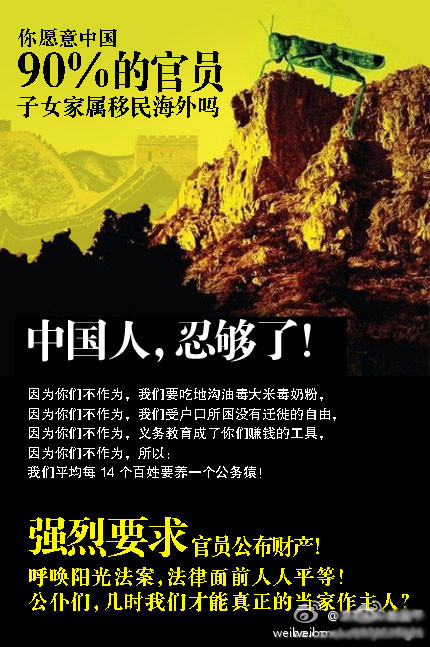

“Do you intend for 90% of China’s officials children and families to migrate abroad?” this one explains. It calls for officials to announce the properties they hold:

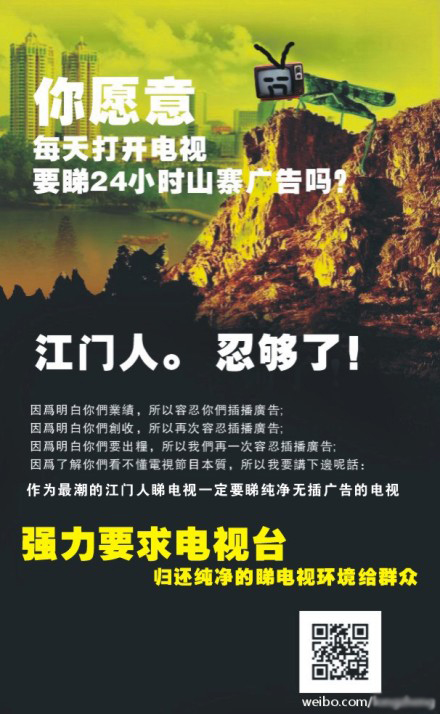

This one calls for residents of Jiangmen in Guangdong to advocate for bootleg-free television:

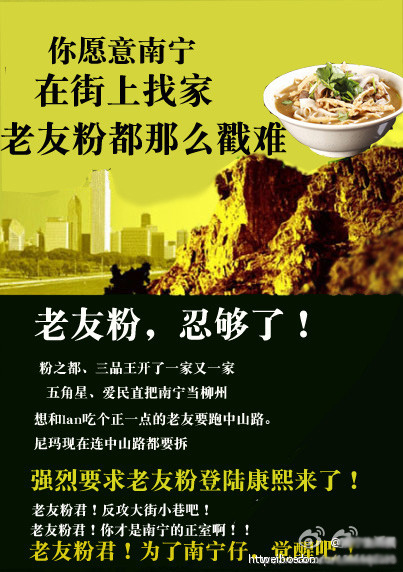

This one worries over the difficulty of finding “Old Friend Noodles,” a delicacy in Nanning that appears to be harder to find on the streets:

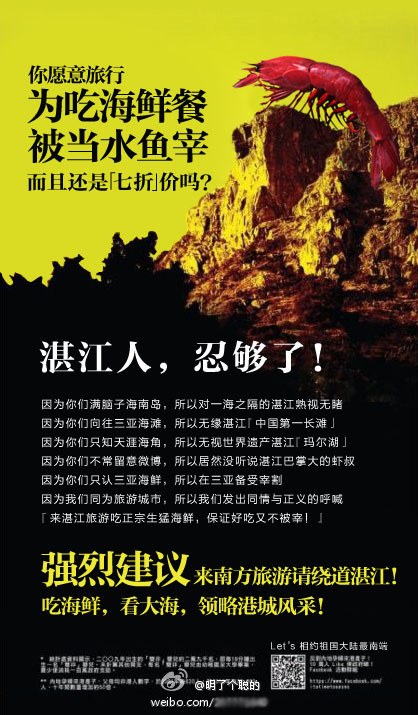

This one advocates for tourists to Zhanjiang to respect the city’s natural graces. Zhanjiang has recently become a tourist boon for seafood and ocean viewing, being just across from Hainan, which China is trying to turn into its own version of Hawaii:

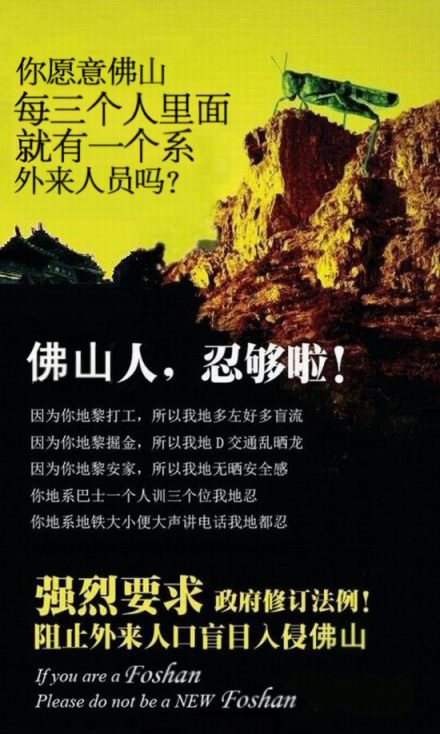

This one expresses concern over the invasion of outsiders into Foshan:

There are so many many more, with cultural references I don’t necessarily understand but which clearly struck a nerve with locals. The locusts meme reveals a host of cultural and regional identities and anxieties, especially in southern provinces with close cultural and economic ties to Hong Kong. It became a perfect tool for venting, and so many reflect the changing dynamics of different cities and provinces as China urbanizes.

But the locusts also reveal a universal truth about memes: animals are catchy. I wrote about the Grass Mud Horse meme. Bear bile has become a hot topic, as Jin Ge explored in a past post, and bear imagery has popped up in protests. I’ll be writing more about the Pandaman meme that Global Voices explored so well. And then, of course, we have locusts.

Just like lolcats and lolruses, advice dog and o rly owl, animals make amazing meme material. In the west, animals are funny and cute. In a place like China, cutesy, non-political animal memes certainly exist. But as the internet is the one place people have to publicly discuss political topics, animals often come with an extra bite. In my next Meme Report, I’ll look at the Pandaman phenomenon and what it suggests about memes in China.